by

THE MURDER OF FOUR RABBIS WAS FELT BY JEWISH PEOPLE

BEYOND THE BORDERS OF JERUSALEM.

IT WAS AN ATTACK ON THE ABILITY OF JEWS TO

ACCESS THEIR HOLY PLACES AND TO PRAY FREELY IN THEIR HOLY CITY.

The medieval Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi wrote of

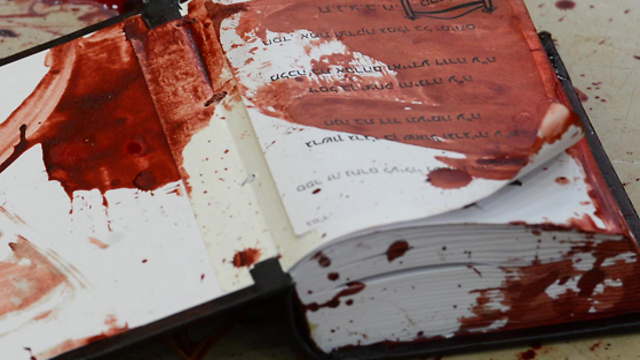

Jerusalem, "it is a golden goblet full of scorpions." On

Tuesday, 18 November 2014, we learnt just what he meant. A sacred site in the

holiest of cities was drenched with the blood of pious men.

The four men murdered inside the synagogue were scholars and

teachers, untainted by violence of any kind. They were men of community and

family, standing in solemn, reflective prayer in a place of worship.

The timing of the attack was calculated to coincide with

morning prayers when the synagogues of the holy city overflow with the devout.

At the very moment when the attack began, the congregants in

the synagogue were about to recite the Amidah, the central prayer of

Jewish liturgy for the last 2,000 years. It calls on a merciful and

compassionate God to forgive sins, heal the sick and bring an end to the exile

of the Jewish people. It asks God to allow the ingathering of the Jewish exiles

back to the land of Israel, rebuild Jerusalem and restore the Kingdom of David

to usher in the period of the Messiah. It concludes with a prayer for universal

peace. The Amidah is recited silently and while standing, preferably

facing Jerusalem, or if one is in Jerusalem, facing the Temple Mount.

Upon entering the synagogue, the terrorists would have

encountered at least ten men, being the quorum required for public worship,

standing silently, with eyes closed. The worshippers were wrapped

in tallit, the traditional Jewish prayer shawl, and some were

wearing teffilin, a set of small black leather boxes containing scrolls of

parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah affixed to the forehead and

upper arm with leather straps. These items symbolise the dedication of mind and

body to God in observance of the commandment in Deuteronomy 6:5-9.

Silence and serenity would have enveloped that house of

prayer as in synagogues throughout Jerusalem and the world, interrupted only by

the sounds of whispered prayers and of the gentle, rhythmic swaying of upright

men deep in meditative prayer.

The son of one of the murdered men, Rabbi Kalman Levine, described

how his father was reciting the Shema prayer when he was killed.

The Shema is the holiest phrase in Judaism, is said twice daily, and

in morning prayers it typically precedes the recital of the Amidah.

"Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one." It is a

declaration of faith and Jewish identity.

The Austrian neurologist and survivor of Auschwitz Viktor

Frankl wrote of the "beings who entered those gas chambers upright, with

the Lord's Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips." They were

also the final words on the lips of the four Rabbis in the Kehilat Yaakov

synagogue in Har Nof.

A police officer attending the scene said that the murders

were remarkable for their savagery. The victims were hacked to death with an

axe and a meat cleaver and shot repeatedly from point blank range as the

terrorists shouted "Alla hu'akbar" ("God is

great" in Arabic). Witnesses outside told of survivors running out with

"half their faces half missing."

The Rabbis all lived on the same street in the Jerusalem neighbourhood

of Har Nof where the massacre took place. Har Nof is in western Jerusalem

within the pre-1967 territory of Israel. The murdered Rabbis leave behind a

widow each and a total of twenty four children to be raised without fathers.

The most eminent of the four was Rabbi Moshe Twersky. A

renowned teacher and scholar, Rabbi Twersky was the scion of a celebrated

dynasty, the son of a Harvard professor of Hebrew literature and the grandson

of the great Rabbi Soloveitchik, considered to be the greatest rabbinical

scholar of the late twentieth century.

The last to die was Sergeant Major Zidan Saif, a thirty year

old Israeli-Druze traffic policeman. Saif was the first officer on the scene of

the attack and was shot in the head by one of the terrorists. Video footage of

the final moments of the attack shows Saif's selflessness and heroism and the

moment when one of the terrorists runs towards the policeman and shoots him in

the face from close range. Saif leaves behind a young wife and a four-month-old

daughter. At Saif's funeral, attended by the Israeli President and thousands of

mourners of all denominations and faiths, Saif's father-in-law recalled a

"heroic man who sacrificed himself for his homeland." A man who was

"worried about his baby, wanted to be near her and would hug her for

hours."

A reporter from the Israeli television network, Channel 2,

went to the Arab neighbourhood of Jabel Mukaber in the south-eastern pocket of

the city, where the two terrorists had lived, to gauge the reaction of the

Palestinian residents to the atrocity. The reporter said he could not find a

single person to condemn the attack. Instead, the murders were praised and

celebrated.

The Jordanian parliament observed a minute's silence - in

honour of the terrorists. Palestinian media was awash with cartoons and

graphics lauding the slayings. Hamas called the attack "heroic."

Several employees of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA),

employed as teachers by the U.N., praised the murders as "wonderful

revenge" and prayed for the terrorists to be accepted in

"paradise" as "martyrs." On the streets of Gaza and in the

West Bank, sweets were handed out in celebration and loudspeakers used for

calls to prayer were blaring words of praise for the murderers.

Palestinian President, Mahmoud Abbas, condemned the murders,

albeit in rather tepid language. Abbas's supporters - such as Palestinian

Legislative Council member, Najat Abu-Bakr, and Fatah Central Committee member,

Tawfiq Tirawi - declared that Abbas's condemnation of the murders was only for

diplomatic purposes, and not sincere. United States Secretary of State John

Kerry said that the attack was the "pure result of incitement" by

Abbas and his Palestinian Authority, which for days before the attack had been

declaring "days of rage" and urging resistance to "Jewish

contamination" of Jerusalem.

From habitual Israel-haters elsewhere there was silence, or

else the usual weasel words about "the cycle of violence," which drew

a false moral equivalence between the measures Israel is forced to take to

protect its people against armed, violent terrorists and the murder of holy men

in a house of prayer.

Israel is no stranger to terrorist attacks against civilian

targets, but this particular attack was especially abhorrent. The victims were

killed as Jews and for being Jews. They were selected to die

because they were the most Jewish, while doing the most Jewish thing - praying

in a synagogue.

The attack targeting a place of sanctuary has again exposed

the vulnerability of Israeli society. The murderers were sending a message that

they plan the same fate for Jews as has been suffered by Christian and other

non-Muslim religious communities throughout the Arab Middle East.

Jews outside Israel, including in Australia, have grown

accustomed to heavily guarded Jewish communal centres and places of worship.

But Israel was supposed to be different. Israel was the safe haven where Jews

could pray and congregate in peace and security. Even

the Guardian for once overcame its generally hyper-critical attitude

towards Israel to state in an

editorial: "The sight of prayer shawls drenched in blood stirs the

bitterest memories. They are the images of a pogrom. The floor of a house of

prayer was turned red."

Indeed, this attack must be understood as an assault on the

freedom to practice one's faith freely and peacefully access sacred holy sites.

This is a right that Israel has been fighting to secure since its creation.

In November 1947, the Palestinian Arab leadership responded

to U.N. General Assembly resolution 181 (II) - calling for the partition of the

British Mandate of Palestine into two States for two peoples - by declaring and

commencing a civil war against the country's Jewish population. This was

followed by a full-scale military invasion of the country by the armies of

neighbouring Arab states. Against the expectations of most, the Jews prevailed.

Egypt, Syria and Jordan signed armistice agreements with the new Jewish state

of Israel.

Under the agreement with Jordan, the city of Jerusalem,

which resolution 181 had recommended become a corpus separatum (separate

body) under international control, became another of the post-war world's

divided cities. Jews and Arabs both rejected the idea of an internationalised

Jerusalem. Israel was recognised as the controlling authority of the western

part of the city and the Jordanians occupied the eastern part, including the

walled Old City and within it, the holy basin.

The Jordanians guaranteed freedom of access for all faiths

throughout the Old City and its holy sites. This commitment was violated from

the beginning. The Jordanians denied all access to Jerusalem's holy sites to the

Jews. 55 synagogues and seminaries in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City were

either sacked, desecrated or entirely destroyed by the Arab Legion. The entire

Jewish population was ethnically cleansed from the area. Free access to

Jerusalem's holy sites for all people was only achieved after the Old City was

captured by Israel in the 1967 war following yet another attempt by Israel's

Arab neighbours to wipe it off the map.

On 19 June 1967, Israel's foreign minister, Abba Eban told

the U.N. General Assembly that while for the period of Jordanian occupation of

Jerusalem, "there has not been free access by men of all faiths to the

shrines which they hold in unique reverence ... Israel is resolved to give

effective expression, in cooperation with the world's great religions, to the

immunity and sanctity of all the Holy Places."

Just weeks after the conclusion of the war, Israel passed

legislation to guarantee freedom of access to all holy places and to protect

them from "desecration and any other violation or anything likely to

violate the freedom of access of members of the different religions to the

places sacred to them."

Israel had control over all of Jerusalem and the West Bank

and was free to administer the Old City and the spiritual treasures within it

as it saw fit. Yet in an extraordinary act of good faith demonstrating its

commitment to free and open worship, Israel agreed that the administration of

the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque would remain with the Waqf (Islamic

religious authority). Surrendering effective control of Judaism's most sacred

site was a truly remarkable gesture, contrasting starkly with the gross abuses

that had been committed by the Jordanians.

Currently, the only impediment to free worship in Jerusalem,

except during riots and other disturbances, is the prohibition on Jewish prayer

on the Temple Mount, the site of the First and Second Temples within which were

located the Foundation Stone and the Holy of Holies. Freedom of access and

worship has endured unaltered since 1967 and despite the existence of a fringe

movement in Israel which calls for a lifting of the prohibition on Jewish

prayer on the Temple Mount, a sentiment that cannot be suppressed in a free

society, the status quo established in 1967 has not changed and

Israeli leaders have consistently refused to alter the current arrangement.

The great tragedy of the Jerusalem synagogue terrorist

attack will not soon be forgotten. It was felt by Jewish people well beyond the

municipal borders of Jerusalem. It was an attack on the ability of Jews to

access their holy places and to pray freely in their holy city. The murders at

Har Nof have transformed Jerusalem. The intrusive apparatus of security will

once again constrict the city as new measures are introduced to protect the

lives of civilians.

Herein lies yet another tragedy. The murders are a blow to

the very possibility of any kind of negotiated peace. Israel has on three

separate occasions made offers to the Palestinians which would have included

Israel and a Palestinian State sharing sovereignty over Jerusalem without

physically redividing the city. The predominantly Arab neighbourhoods of the

city and the surface of the Temple Mount were proposed as a part of the

Palestinian State. It is unlikely that Israel will ever renew that proposal.

Such an arrangement presupposes that both Jews and Palestinian [Arabs]s in the city

could be safe and secure without being physically separated. That prospect now

seems more distant than ever.